Regelbau – bunkers as standardised structures

Most of the bunkers built along the west coast of Denmark as a part of “The New West Wall” or “The Atlantic Wall” starting in summer 1942 were of the Regelbau type.

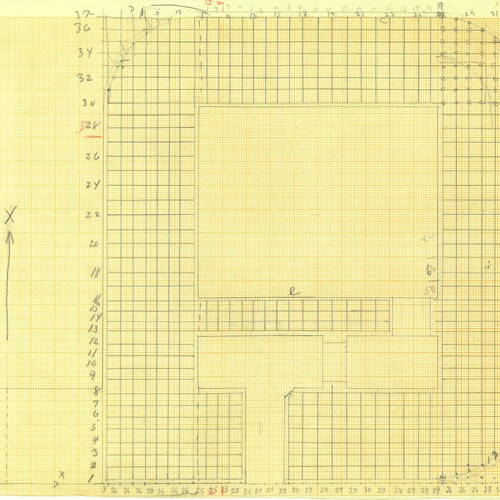

Regelbau was the name of a system of standardised bunkers developed at central level by the German High Command. Bunkers of this kind could be built anywhere, with minor modifications, and the standardisation made it possible to streamline the planning and construction work to a high degree.

The Regelbau system was introduced in the latter half of the 1930s for use on the original “West Wall” along the border between Germany and France.

Construction of “The New West Wall” was a much more comprehensive project, however, requiring bunkers that could fulfil many more functions. As a result, the system was developed to include a whole range of different types of bunker. In all, bunkers of around 250 different Regelbau types were constructed as part of the “Atlantic Wall”.

The standard bunkers were built in three different “construction strengths”:

Permanent (ständig): walls and roofs 1.5–3.5 metres thick

Reinforced field (verstärkt feldmässig): walls and roofs 1 metre thick

Field (feldmässig): walls and roofs 0.3–0.6 metres thick.

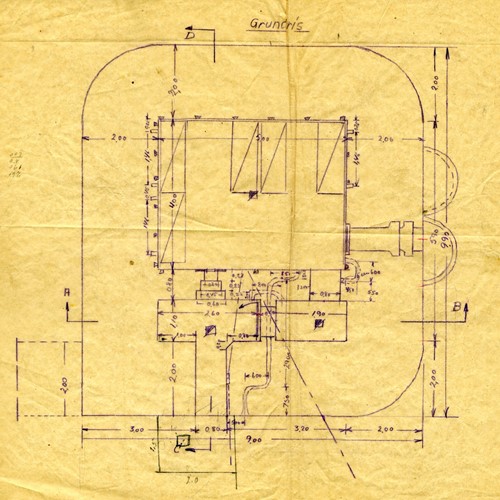

Interior layout of the Regelbau bunkers

Even though the Regelbau bunkers were built to fulfil a variety of functions, many aspects of their interior layout and design were standardised and replicated in all the various types.

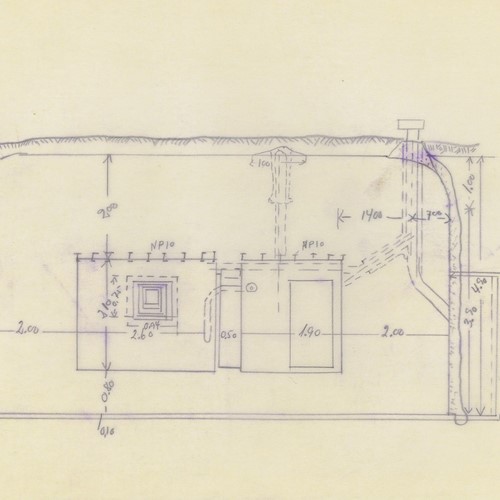

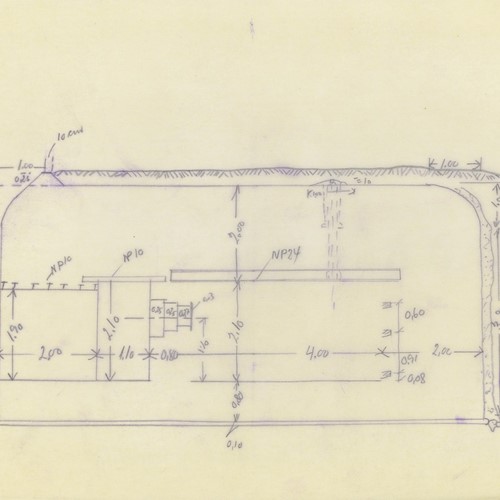

The entrance was almost always guarded by a gun slit in a 3 cm-thick armoured plate at the end of the entrance corridor. Bunkers that were to be crewed during battle generally also featured an extension on the façade with gun slits to enable the defenders to shoot closely along the exterior bunker walls.

Located to the right or left of the gun slit, the entrance door to the bunker was a 3 cm-thick armoured door in two sections.

After the entrance was an air-lock, a type of “mini-hall” where in the event of a gas attack, people entering from the outside had to wait until the overpressure in the bunker had replaced (i.e. cleaned) the air in the air-lock. They could then enter the bunker without allowing gas to penetrate the interior.

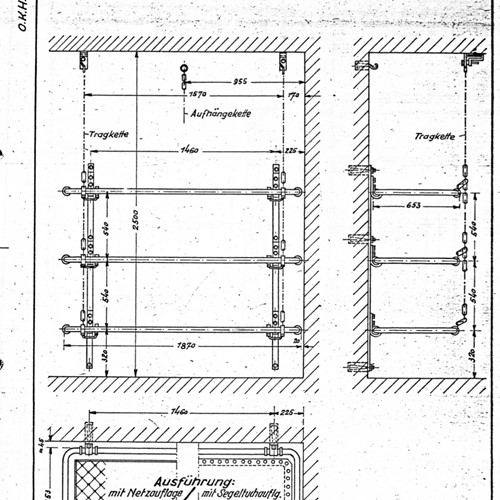

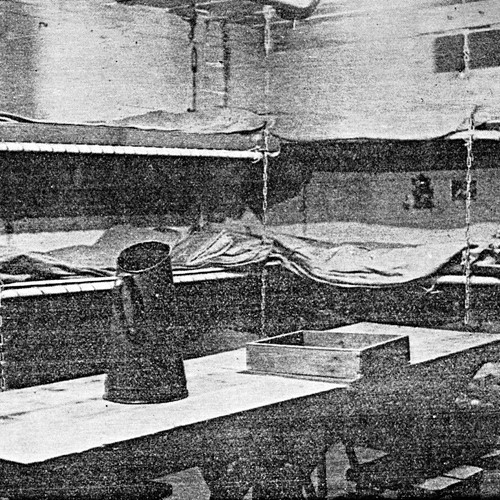

The crew quarters in the bunker were extremely cramped; generally speaking, there was only around 2 square metres of floor space per man. The soldiers slept in three-tier bunk beds made of iron frames and secured to the walls by 3–4 bolts at each end. The mattresses were made of sacking cloth stuffed with crimp wool. To help keep out the cold, the wall behind the bunks was often insulated with softboard panels or wooden planks.

Wooden tables and stools stood in the middle of the room, and the walls were lined with wooden lockers for the soldiers’ equipment.

As a rule, the bunker rooms were heated using a gas-tight, pressure-tight iron stove that was kept lit all year round to fight off the cold and damp. The stove also had a hot plate that the soldiers could use to heat their meals.

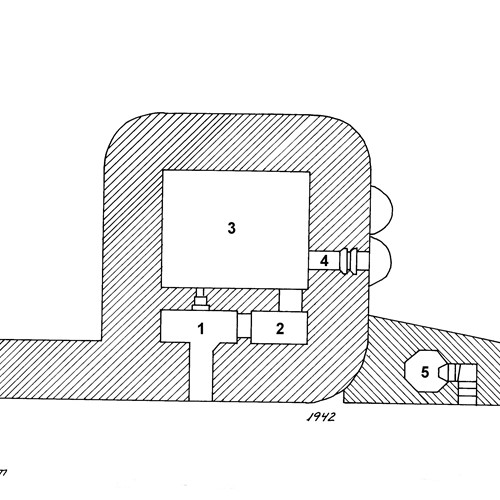

The flue pipe from the stove was designed to prevent attackers dropping hand grenades directly into the bunker from above. There was a branch in the pipe that led any hand grenade along the outside of the wall, dropping it into an “explosion pit” where it would do little, if any, damage.

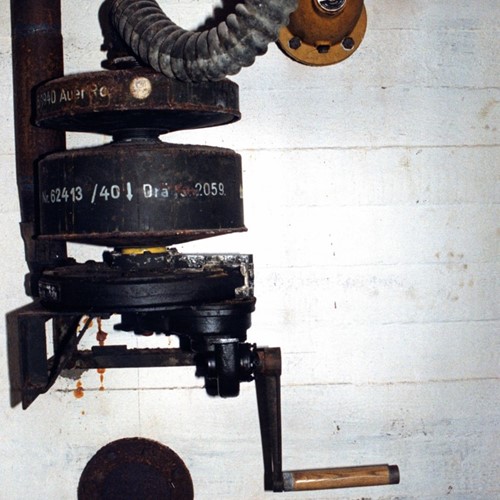

The crew quarters were fitted with a ventilator unit with a capacity of up to 1.3 cubic metres per minute. This unit was normally operated manually, but it was also possible to fit an electric motor to it. The bunker could be sealed completely in the event of a gas attack. The air drawn into the bunker was purified using a carbon filter fitted to the top of the ventilator unit.

The ventilation openings were located on the front of the bunker, and they were covered with sturdy grilles to prevent attacking forces from throwing hand grenades into them.

The ventilation unit was not only used in the event of gas attacks, it also took care of the everyday ventilation of the bunker. In fact, the crews had to run the unit for ten minutes every morning to maintain a tolerable level of air quality inside the bunker.

Electric lighting was installed in the bunkers. However, given that the electricity was supplied by external cables and few bunkers had their own generator, it was to be expected that the power supply would be cut in the event of bombing or shelling. The crews therefore used battery-operated torches or carbide lamps to supplement the interior lighting.

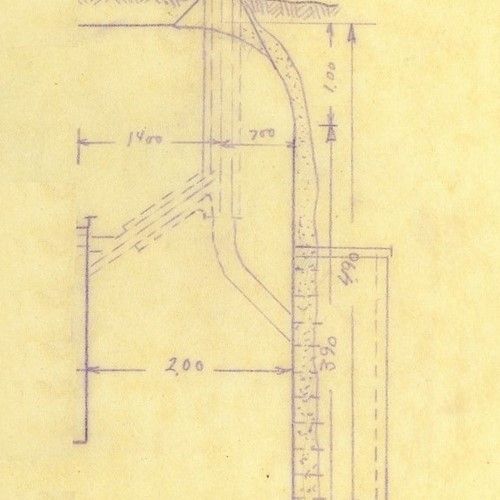

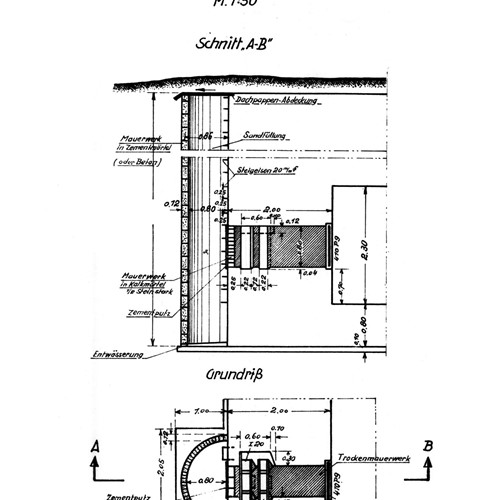

Bunkers with only one entrance featured an emergency exit in their side wall so that the crews could still exit them if the main entrance became blocked by soil and rubble. The emergency exit took the form of a horizontal shaft running through the wall and ending in a horizontal shaft in the outer wall of the bunker. The entrance to the horizontal shaft from the bunker room was sealed with an iron hatch, and the shaft itself was filled with loose bricks and two transverse iron beams that could only be removed from the inside. Facing the horizontal shaft was a half-brick wall. This shaft was also filled with rubble that would have to be emptied before the crew could exit.