History of the Atlantic Wall in

Denmark

As soon as the occupying German forces reached the north and west coasts of Jutland in Denmark, they started building fortifications.

The number and strength of the fortified installations was closely aligned with the level of threat to German control of Denmark that the German High Command believed to exist.

It was for this reason that the fortification of Denmark by the German forces underwent radical development during the occupation of 1940–45: from flimsy wooden buildings to huge concrete bunkers with walls and ceilings up to 3.5 metres thick.

The first coastal batteries

Immediately after subjugating the country, the occupying German forces started work on installing gun emplacements intended to guard the newly conquered territory against counter-attacks from British and Allied forces. The defence measures initially involved mobile batteries from the army and navy, which were set up in temporary field positions.

The guns were positioned to protect especially important harbours and coastal waters, and a large number of mines were laid at sea to cut off the approach to the waters of Skagerrak between Hanstholm in Denmark and Kristiansand in Norway.

Permanent coastal batteries

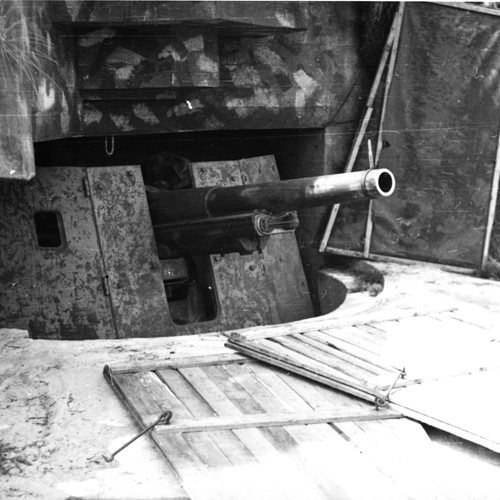

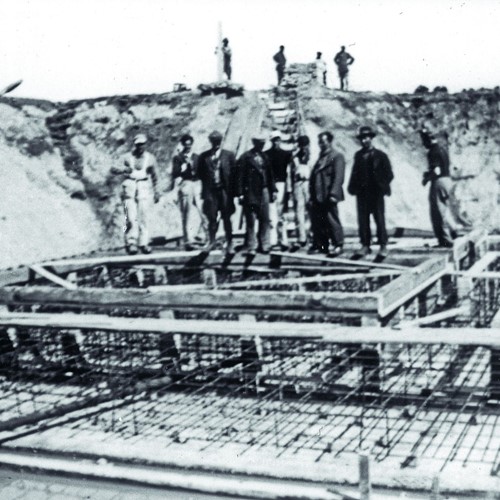

Just a few days after the successful invasion of Denmark, the German Navy started building its own, permanent coastal batteries. The navy’s coastal artillery consisted of former naval guns so engineers had to construct concrete foundations and similar installations before the guns could be seated. As a result, the first naval batteries were not reported ready for action until May/June 1940.

The first coastal batteries did not actually resemble fortified positions. Apart from the foundations, little concrete was used in the batteries and the battery crews were billeted in wooden barracks close to the guns.

Heavy batteries to Denmark

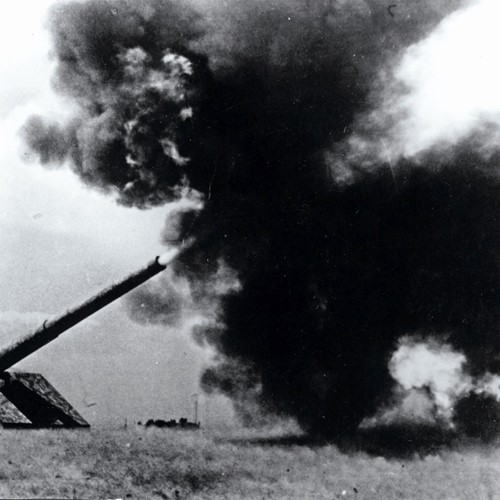

In November 1940, the German forces began constructing heavy batteries at Hanstholm and at Dueodde on the island of Bornholm, south of Sweden. The Hanstholm Battery was tasked with sealing off the approach to Skagerrak, while the battery on Bornholm was to protect shipping in the Baltic Sea from possible Soviet attack. The guns at the Hanstholm installation had a range of 55 km.

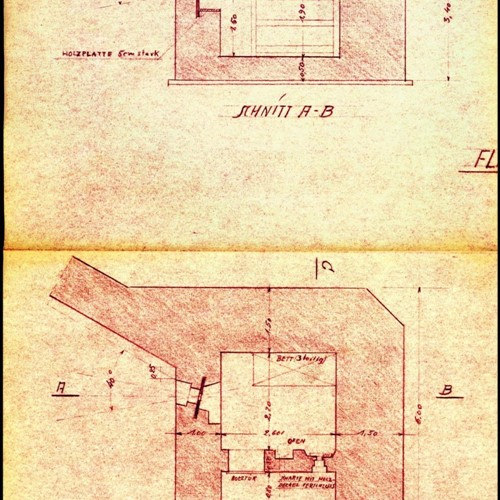

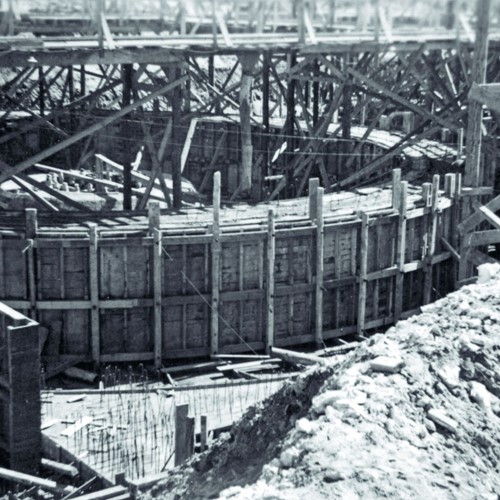

It was a huge project that included the construction of four giant bunkers for the guns themselves. Each bunker covered an area of approximately 2,000 square metres, and comprised not only magazines for the gun ammunition, but also living quarters for the 90-strong gun crews.

Army coastal batteries

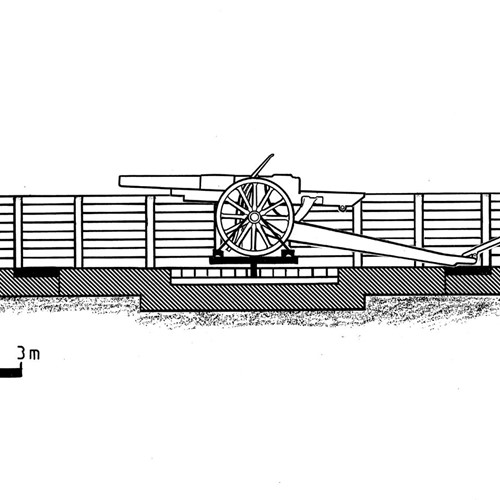

A large number of new coastal batteries were built in Western Europe in the summer of 1941. The new installations were intended to compensate for the huge numbers of troops that were being moved east in preparation for opening a second front against the Soviet Union. A commitment of this magnitude was too much for the German Navy, so the guns – often the spoils of war – were supplied by the army and the batteries were designated “army coastal batteries”.

Ten new batteries were set up in Denmark, all equipped with French field guns from the First World War. Six of the batteries were immediately installed along the west coast of Jutland, while the remainder were positioned close to the internal coastal waters and only moved to the west coast towards the end of 1941. Five of the batteries were sited north of the Limfjord.

"New West Wall"

By the autumn of 1941, it was clear that the German offensive against the Soviet Union had ground to a halt, which meant that the majority of the German army would remain committed to the Eastern Front. As a result, Adolf Hitler decreed in December 1941 that the coastlines of Western Europe were to be fortified as a “New West Wall” so that any attack could be beaten back.

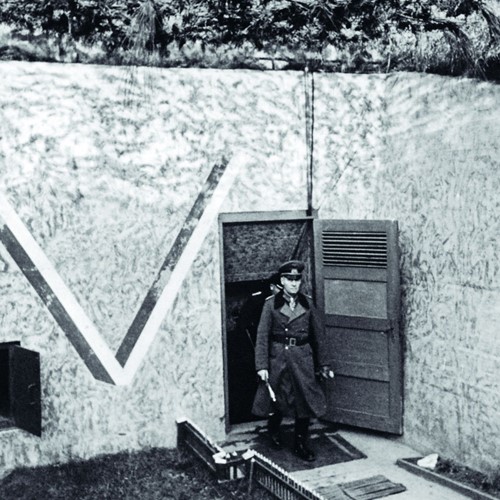

Hitler’s orders to build a “New West Wall” led to a flurry of activity along the coast of Jutland, with more men and equipment being relocated to the region. The biggest new initiative, however, was the start of work on huge, heavily armoured bunkers. Up until this point, the batteries had comprised only wooden barracks and a few bunkers built of wood or thin concrete, but the army engineers were now building bunkers with walls 2 metres thick for all the coastal batteries.

Strong points

In the summer of 1942, the German army troops were moved closer to the coast. Special “strongpoints” were set up for companies of infantry at key locations along the coastline, particularly in places with important traffic connections: Agger, Løkken and Hirtshals, for example.

Initially, the troops dug in – literally – in trenches reinforced with wood, but solid concrete bunkers were gradually built at most of the strongpoints. These bunkers were intended to provide quarters and kitchen facilities for the troops, and to protect water supplies, hospitals and the like.

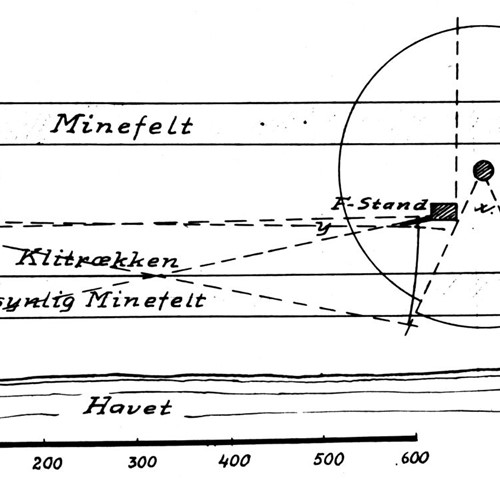

The strongpoints were surrounded by all sorts of barriers and obstacles designed to hinder enemy forces and prevent them from penetrating the actual strongpoints.

The outermost defences consisted of minefields hundreds of yards wide and featuring a mix of anti-tank and anti-personnel devices.

In some places, the minefields were backed by tank traps – wide trenches approximately 2 metres deep designed to stop tanks in their tracks.

After the minefields and tank traps came broad barbed-wire barriers and rows of anti-tank obstacles made of metal angle beams. As these obstacles originally came from Czechoslovakia, they were known as “Czech hedgehogs”.

Behind the minefields, barbed-wire fences and other obstacles, the troops were armed with a variety of light and heavy weapons to prevent the enemy overrunning the position.

Inspection by Rommel

Towards the end of 1943, the German High Command was seriously worried about a potential Allied invasion of Western Europe – with Denmark high on the list of potential landing sites.

In order to improve the defences, Hitler dispatched his famous Field Marshall, Erwin Rommel, to inspect the “Atlantic Wall”. Rommel initiated his tour of inspection in Denmark.

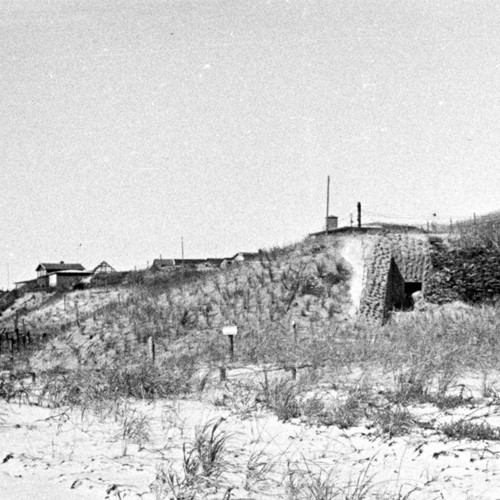

On his travels in Denmark, Rommel developed a number of new principles for the structure of the country’s defences. Up until now, fortified positions had only been established in particularly important locations, but Rommel wanted to fortify the entire coastline so that any attempted invasion could be halted before it even left the beach.

Following the inspection by Rommel, work was started on expanding the fortifications along the coast from Esbjerg to Thyborøn so as to create an unbroken line of defence. The work took the form of setting up barbed-wire obstacles and laying mines on or behind the beach. In addition, a large number of small bunkers were built along the edges of beach borders, with slits for machine guns to fire through parallel with the coast – “flanking bunkers” as they were known.

New coastal batteries

On account of the orders to reinforce the coastal defences, the artillery positions along the west coast were significantly strengthened. At the beginning of 1944, ten new army coastal batteries were established in Denmark, as well as five new coastal batteries operated by the navy.

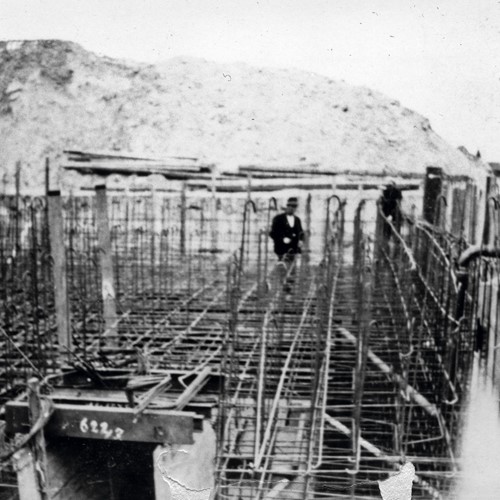

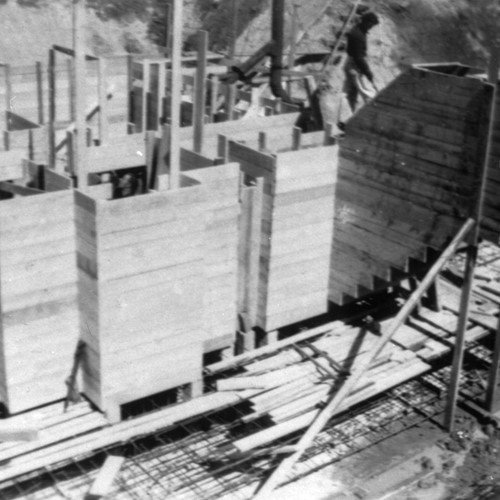

In the spring of 1944, most of the guns from the old coastal batteries were re-seated in robust concrete bunkers. The intention was to protect them and their crews from heavy shelling and bombing from the air and sea which would almost certainly be used as the precursor to any invasion. The heavily armoured bunkers provided good protection, but limited the guns’ field of fire to just 120 degrees.

Reinforcement along the Kattegat coastline

It might have been expected that work on fortifying the west coast of Denmark would have come to a halt following the Allied landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944. The situation proved to be quite the reverse, however, with the German Navy redoubling its efforts to reinforce the coastal defences along the shores of the Kattegat. The new push involved measures including bringing in a large number of light and medium batteries. Over the course of autumn 1944 and the first few months of 1945, fully 28 new batteries were established along the Kattegat coastline.

The reason for the spike in activity was the desire to protect the seaward approach to the Baltic Sea, which had been accorded even greater priority by the German Navy following the loss of its bases in France. If the Allies succeeded in blocking access to the Baltic, the German Navy would no longer be able to dispatch its U-boats to the Atlantic; moreover, it would simultaneously lose its training grounds for new U-boat crews.

![1992 – Regelbau 622, bunker, Søndervig].jpg](/media/1427/1992-regelbau-622-bunker-soendervig.jpg?anchor=center&mode=crop&width=500&height=500&rnd=132064567090000000)